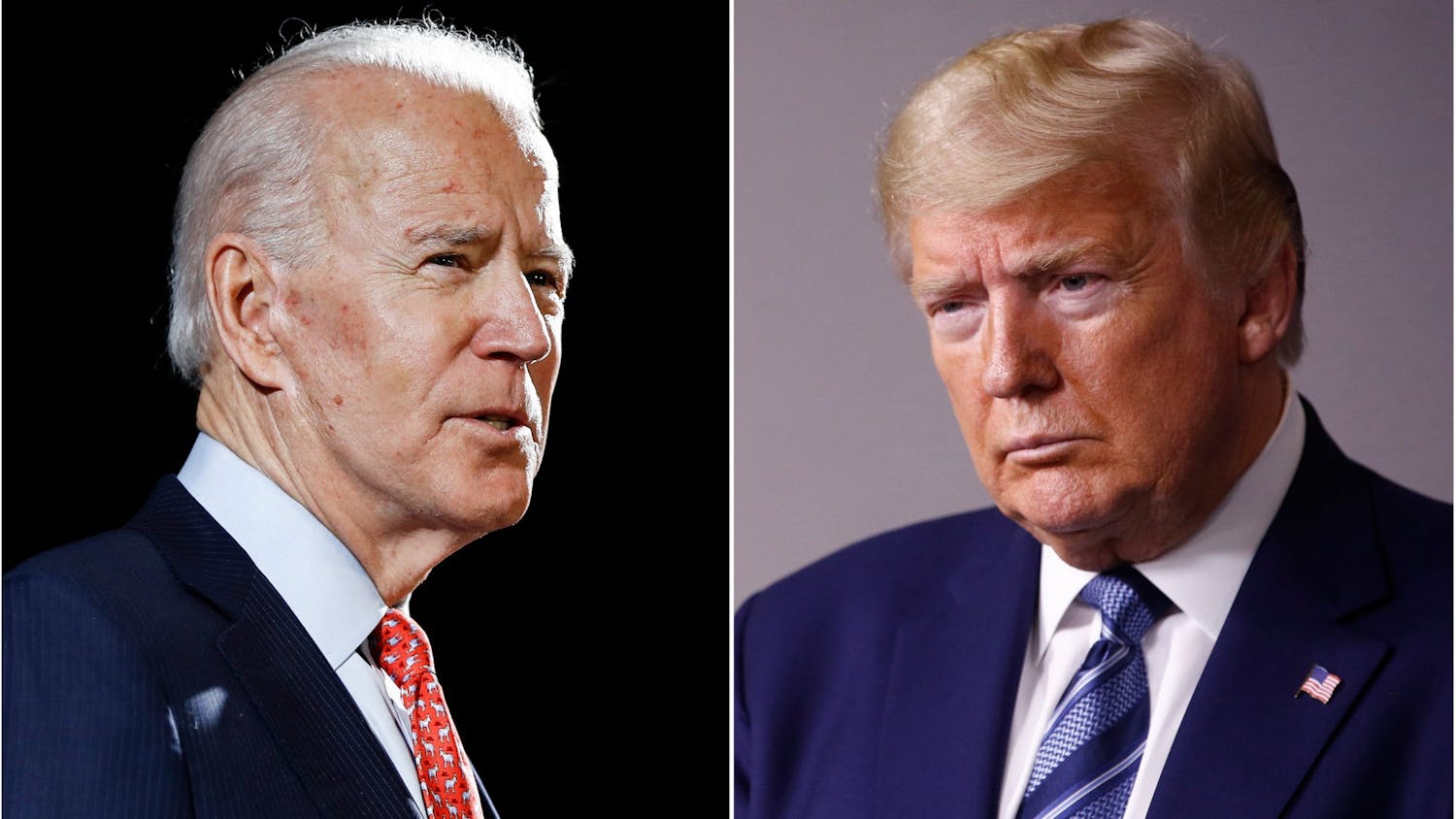

The first presidential debate was relatively widely panned. Large stretches of time were completely unintelligible as the two candidates talked over one another and threw personal attacks. Partisans on both sides announced their candidate’s victory while commentators bemoaned the lack of civility and substance, and worried about the implications for our democracy. Most people tuned out quickly.

But, to my knowledge, neither Trump nor Biden accused the other of being a corpse.

It’s easy to get caught up in the heated language and strong feelings of modern politics, and assume that we are a nation on the brink. How can a nation of the people stand when the people won’t stand together? But this fear — as understandable as it might be — betrays a lack of perspective.

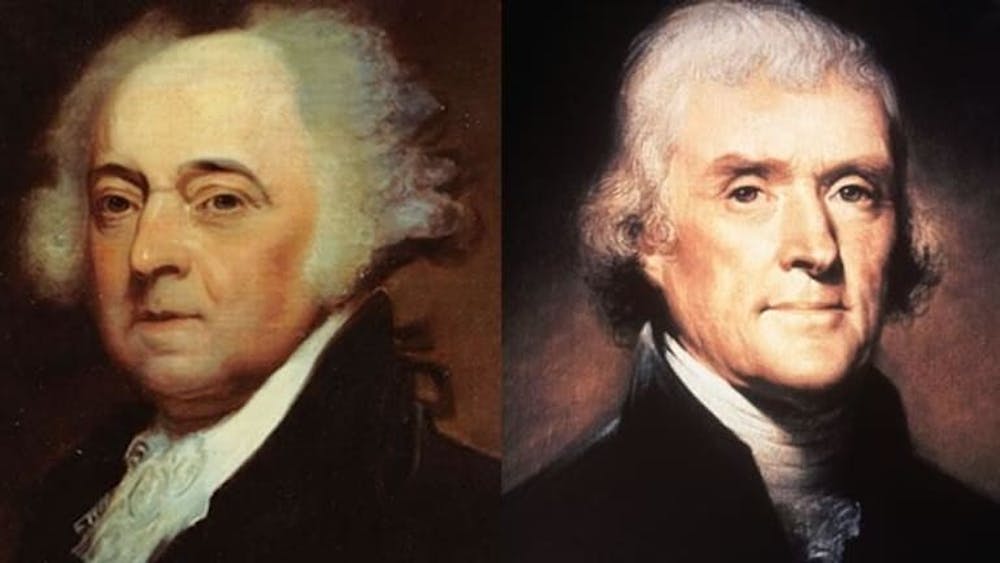

In 1800, Adams described his opponent, Jefferson, as a godless firestarter who promised disaster if elected: “the air will be rent with the cries of the distressed, the soil will be soaked with blood, and the nation black with crimes.” In turn, Jefferson described Adams’ secret plot to install himself as King of America. Adams retaliated by spreading rumors of Jefferson’s death — for my money, an unparalleled piece of negative campaigning. The election of 1800 was by no means the worst, either. See Swint’s book “Mudslingers” for plenty of sordid stories.

Of course, it might be cold comfort to simply point out that things have been worse before. It doesn’t help to tell someone who’s lost a leg that others have lost two. But we can take two lessons from this, at least: first, that loud political arguments can often exaggerate the actual degree of political division the country faces.

In 2019, Professor Morris P. Fiorina published “Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America.” His controversial argument was that Americans are no more polarized today than in the days of Jimmy Carter. The parties might be more polarized, the elites might be louder about pointing out divisions that exist — but Americans today thought pretty much the same things as they did back then. The More in Common project, a massive survey of American political views, supports this view: while they find small groups of outspoken partisans who are very public about their dislike for the other side, the vast majority of Americans have strong, quiet political views coupled with a healthy respect for free expression, differing views, and compromise. Not moderates or centrists, but rather humble in their convictions. The debate, in other words, is most likely not an accurate picture of how we truly feel about our neighbors.

Second, our democracy is robust to strong disagreement. In fact, it thrives on it. A Federalist in the election of 1800 is quoted by historians as expecting the fierce division in that election to doom the nation to “convulsions, changes, and calamities”. Yet, like all such fierce elections, things rapidly settled back down – and reforms in the aftermath of that election made our political system stronger in the long run.

Trees need stress to grow strong, as the Biosphere 2 experiments showed. Similarly, our political system was forged in a period of extraordinary political division – Madison described Americans in Federalist No. 10 as “much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to cooperate for their common good”. Our country is designed, therefore, to not only survive but thrive in such an environment. Honest, humble, and loving disagreement and discussion helps us grow.

None of this is to excuse or glorify name-calling, insults or political bomb-throwing. If you are concerned about the state of modern political rhetoric, you’re right to be. But hopefully we can approach this problem with a sense of scale, love for those we disagree with, and confidence in a system founded on free expression.