Taylor faces lower enrollment numbers than expected alongside a significant budget deficit this year.

Information provided by Steve Mortland, vice president of enrollment and strategic institutional engagement, showed that 531 freshmen came to Taylor fall of 2018. This year the university budgeted for 505 freshmen, but 490 enrolled. For 2013-17 enrollment numbers varied from 435 to 521.

The university also currently operates with a budget deficit of approximately $2 million. For the past seven years, the university has typically generated a deficit, but that deficit has totaled around $2 million for the past three years according to Stephen Olson, vice president of business and finance.

“When a class comes in you are looking at two things,” Mortland said. “You are looking at headcount, and you are also looking at how much did you spend in discount to recruit those students.”

Mortland said that no matter what a school budgets, any percentage of variance creates large financial results.

Student persistence rates, which tracks a student’s retention through their four years at Taylor, for upperclassmen also affect the budget. Taylor expected a persistence rate of 88%, but it fell to 86% for the class of 2022. Both Mortland and Olson put the national average around 56%. The class of 2021 also underperformed by one to two percent.

Taylor also raised its academic standards. In previous years, Taylor allowed a greater number of students with a certain level of academic risk due to lower ACT or SAT scores.

“These are not students who are less capable of being successful at Taylor,” Mortland said. “They just might need more support.”

Mortland said that the larger number of students who needed greater support overtaxed Taylor's support resources such as the Academic Enrichment Center. Since these systems could not appropriately help these students, fewer students with academic risk were accepted.

Having a lower number of students with academic risk lowered the total count. That pairs with a class that earned slightly institutional merit scholarships due to higher ACT and SAT scores to significantly widen the deficit.

“Anytime you use past experience to predict for the future, you’re subject to the whims of change,” Olson said. “There’s a time where we would go back and use a ten-year history to make these projections. The world of higher education is radically different than it was five years ago, ten years ago.”

Both Mortland and Olson referenced the general shift in higher education occurring among all colleges. A variety of alternatives exist beyond a four-year degree, and they cause financial strain on institutions like Taylor.

Mortland also said the decline in the North American church specifically affects institutions like Taylor or its sister schools.

“Sometimes you may need to stay on your current expense path because you know, or at least you believe, that things will change because of things that you are doing that will improve your revenue situation,” Olson said in reference to rectifying the deficit. “So don’t cut out those expenses because they’re necessary to get you to that point in two years.”

Olson believes that Taylor must continue spending necessary funds on its programs despite the deficit. By investing in Taylor programs, the university will draw in students. He said Taylor has time since it has a strong financial foundation.

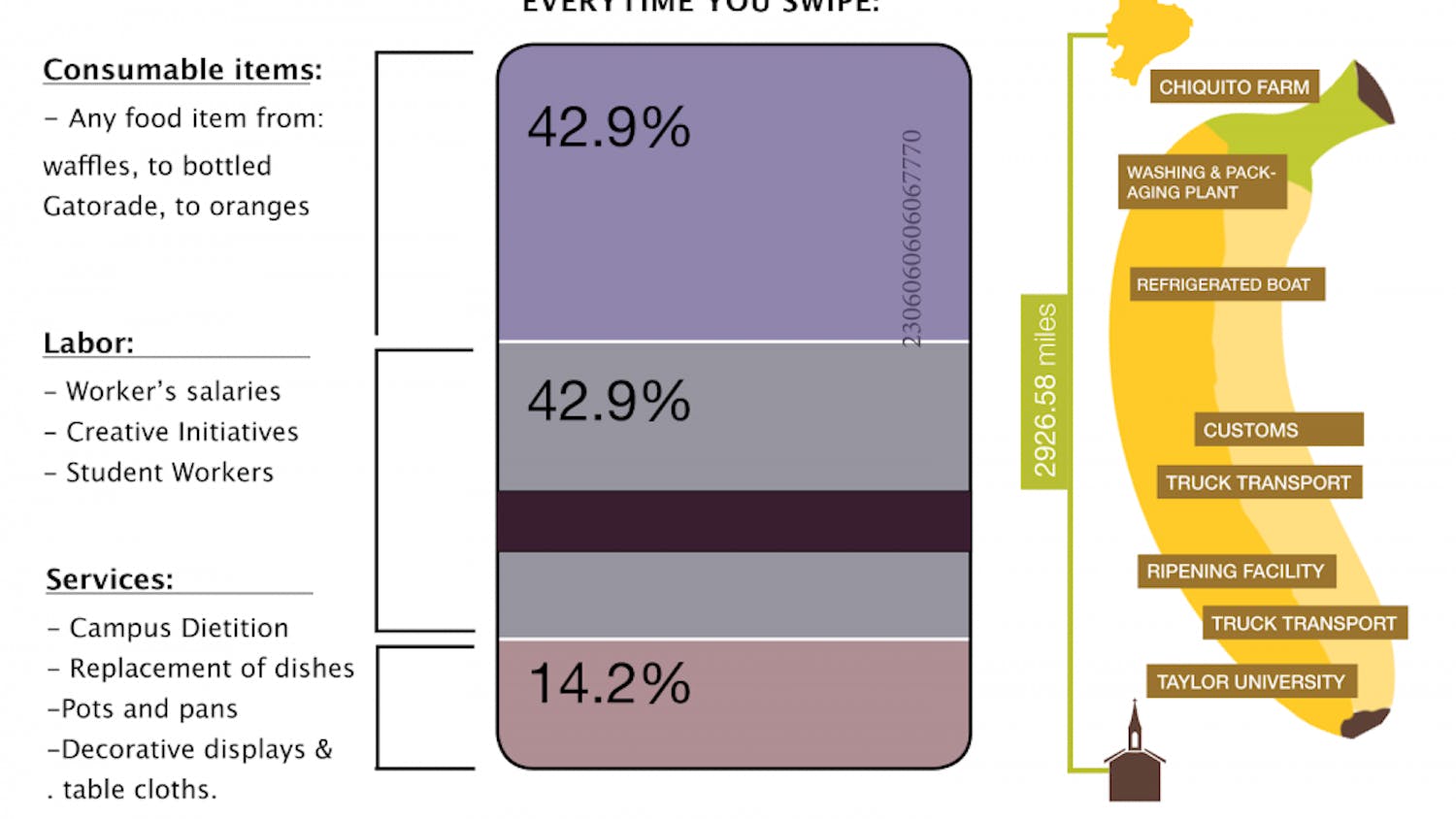

Mortland said students directly affect Taylor’s enrollment by giving testimonials of their experiences to high schoolers. Olson stressed little steps like eating responsibly at the DC or respecting campus facilities; both affect the budget.

“When Taylor’s handled it best, one we’ve not panicked,” said Tom Jones, dean of humanities, arts and biblical studies. “ Two, we’ve taken stock of what we do best in comparison to what students want. We don’t try to change who we are.”