Abigail Roberts | The Echo

Taylor sits in the middle of a food desert.

A food desert is an area with low local access to fresh produce and foods. Unbeknownst to many local residents, Aggressively Organic estimates that every county in Indiana struggles with food insecurity. This includes Taylor University's very own Grant County.

According to Walk Store, Indianapolis is ranked number one as the worst city in the U.S. for food access. Food access means at least a five-minute proximity to a grocery store, according to Food Access Research Atlas.

"(In) this area it's really hard . . . they call it a food desert because there's nothing being grown here except for their main agriculture farms," Creative Dining Associate Director and Executive Chef Nathaniel Malone said.

The fields of corn and soybeans students pass while driving to and from Taylor are not accessible to local purchasers. The majority goes toward industry. Only 10 percent of Indiana corn crops go toward human consumption; 36 percent goes to animal feed and 26 percent toward ethanol production according to the Indiana Corn Growers Association (ICGA).

Indiana also lacks any form of agricultural biodiversity, with little produce variety. The ICGA reports that corn and soybeans jointly make up 82 percent of the state's agricultural exports.

If Taylor sits in the middle of a food desert, then where do student's fruits, vegetables and other foodstuffs come from?

The majority of the Dining Service's produce comes from Michigan through Gordon Food Services, the largest family-managed foodservice distribution company in North America, according to Gordon Food Company. Trucks carrying shipments cycle through three times a week. Supplemental fruits and vegetables are shipped in from Produce Alliance twice a week.

"It is a supply and demand problem," Malone said. "People expect a certain variety in their food."

Produce is shipped in rather than locally sourced for two reasons: students' unrealistic expectations of food variety and the scarcity of accessible local produce farms.

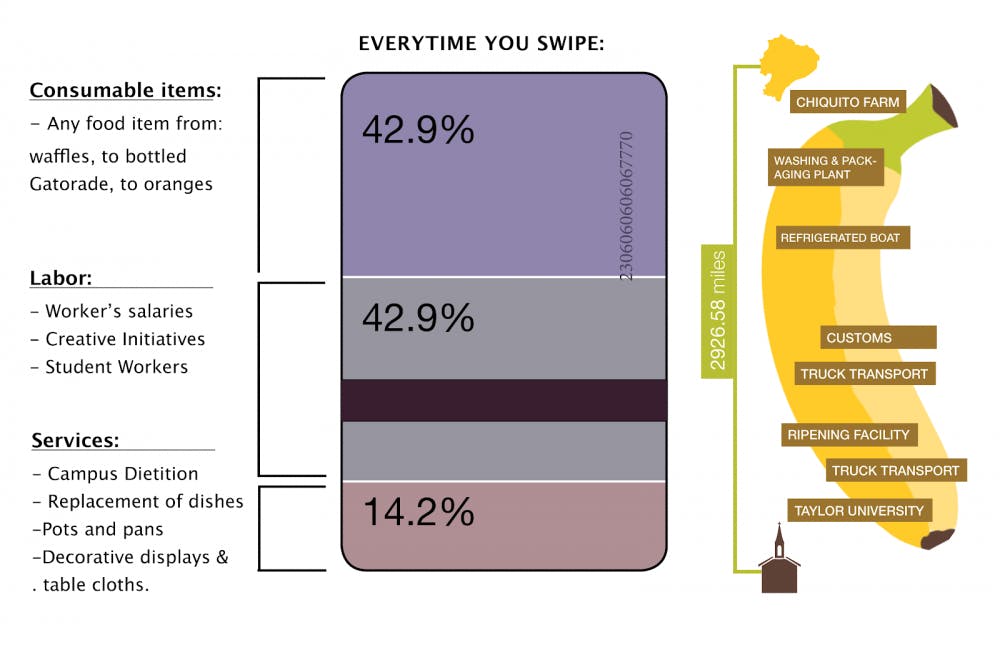

For example, bananas are not currently in season nor are they local. Yet Taylor students have access to them at every meal.

"It would be nice if there was more education among students on seasonality," Malone said. "We've lost a lot of what we used to know about food . . . We're no longer hunter-gatherers, we consume."

Outside of their main shipments from large food vendors Malone also reaches out to local vendors as much as possible. The majority of his organic local purchases go toward catering as they are too small for the entire student body.

He purchases everything Taylor's campus garden offers, and as much fresh produce from Victory Acres as possible. However, neither are consistent or provide a high enough quantity to feed 2,000 students. Malone primarily uses their produce in Taylor's catering meals.

"I tell them, 'I'll buy anything you bring me,'" Malone said. "They once brought me pounds of basil which I put in our freezer to use for pesto."

Malone previously worked at Butler University. Closer to Indianapolis, Malone had a wider variety of fresh food options thanks to recently increased initiatives like farmers markets and community gardens there.

Malone and Assistant Professor of Sustainable Development Phil Grabowski are working to help small farms like nearby Victory Acres increase production and therefore become more sustainable sourcing partners.

"We could produce a lot more if we wanted to (with the Taylor garden)," Assistant Professor of Earth Environmental Science Rob Reber said. "A lot of it is timing. Most produce is grown over the summer when the students who could do the work are on break."

Victory Acres Farm has the capacity to produce year-round produce, but lacks labor. Grabowski would like to initiate more students' interaction by including it as part of his curriculum.

Malone is also actively looking into other local vendors as far as Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Vice President for Finance Stephen Olson is in favor of local options, but values weighing the costs and benefits.

"I know Nathaniel is investigating local options, and I favor local food sourcing, but it comes at a premium," Olson said. "We have to ask, is it more important to shop local or use that same money to do something else on campus?"

Taylor University's food budget is seven million dollars a year. Student's payments of $4,560 for board for the 2018-2019 school year make up the majority of the budget. A student's board payment is their meal fee.

For example, Taylor pays Chick-fil-A royalties to have its popular brand name franchise on campus. Additionally, Taylor's addition of five meal swipes a week for all students in the campus center created a need for more employees to manage the new traffic.

According to Olson, this year approximately 30-40 percent of all student meals are eaten at the student center compared to last year's 15-20 percent.

"You also need to add to the cost every time students take out extra food," Olson said. "They budget for the amount it's going to cost to feed each student. Every time something happens to feed that food cost, prices go up."

When students go into the Dining Commons without scanning or take more than the one piece of fruit, it adds to the food plan's overall costs.

Food variety is a luxury, not a normality. So, while students peel their bananas, eat their burgers or eye a salad, consider how long it took to get to middle-of-the-cornfields Indiana.

"The mindset of the student is going to drive the realities of the physical," Reber said. "We have a social responsibility to sustainability."