By Alex Mellen | Echo

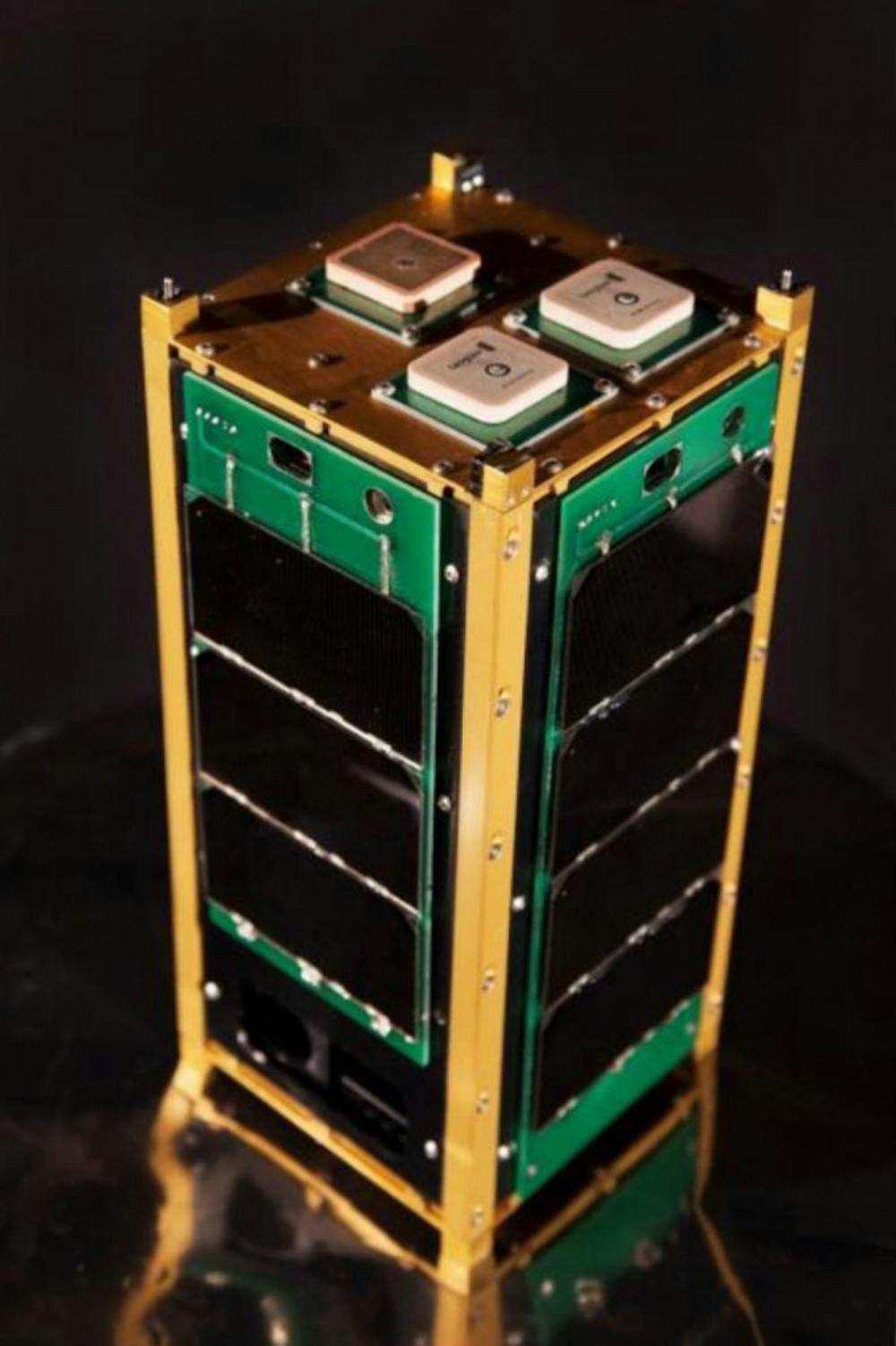

After several delays, Taylor's nanosatellite TSAT successfully launched April 18 and is now transmitting data to Earth. A SpaceX rocket carried the Dragon craft and was NASA's fourth attempt for this mission.

TSAT is now zipping along in orbit at almost five miles per second, circling the globe every 90 minutes at 200 miles above the Earth. At that speed, it could travel from Upland to Chicago in just over a minute.

It is the first satellite completely designed and built in Indiana, according to the Physics Department.

It was created to link satellites without a ground-based relay and to collect scientific data from the ionosphere, an area of the upper atmosphere where few other researchers have collected data, according to physics professor Jeff Dailey.

"It is a very good area to be doing research," Dailey said.

Once in space, Dragon released TSAT and three other university-built nanosatellites to begin their missions. According to senior Tom Sargent, TSAT began transmitting data between 11-30 seconds after powering on.

"What we've seen is that our new communications on TSAT are incredible compared to other groups," Sargent said. None of the other satellites deployed have transmitted significant data, he added.

Taylor partnered with GlobalStar, a commercial company managing several orbiting satellites, so TSAT can relay its data to nearby GlobalStar satellites and from those to Earth. This is the first time in history a commercial nanosatellite has communicated in this way with other satellites.

The satellite's expected lifetime is eight weeks before it burns up in the low atmosphere, about 100 miles up. According to estimates by NASA, it will outlast the other three nanosatellites.

Dailey delivered TSAT to NASA last December, after several undergraduate students did final work on it last summer. Sargent, Matt Orvis ('13) and seniors Joe Emison and Adam Kilmer traveled to Florida for the scheduled April 14 launch. However, it was postponed less than a hour before liftoff due to a helium leak in the rocket.

Sargent did not contribute to TSAT but currently works on ELEO-SAT, Taylor's next satellite contract. Last year's seniors worked on TSAT for their senior project, and many are now benefitting from the experience in their jobs and at grad school.

Students have also shared authorship of research papers that have been published by prestigious organizations such as the American Society for Engineering Education.

"That's extremely significant for any futures in either graduate school or jobs," Sargent said.

TSAT's successful performance also gives credibility to ELEO-SAT, Dailey said.

Dailey and Air Force analysts have begun verifying the data's quality, but the bulk of it will be analyzed by students starting this May and continuing into the summer. According to Sargent and Dailey, the entire process could take up to a year.

But the most important work has already been done.