By Luke A. Wildman | Contributor

Do you ever engage with a piece of art and go, "What was that?"

You know what I'm talking about. The song lyrics that seem like gibberish, despite being English. The "experimental fiction" story that you'd need a PhD to understand. I'm not talking about classics, art that was created for a different audience or even art that's difficult because of its subject. I'm talking about art that's intentionally difficult.

I'd like to tell you a story about this. I just met the most extraordinary gentleman.

This semester I've been studying abroad in York, U.K. Often, before class, I wander through the Shambles, an old street of cobblestones and crooked buildings where the "Harry Potter" films' Diagon Alley scenes were filmed. Scents of chocolate and roasting meat suffuse everything.

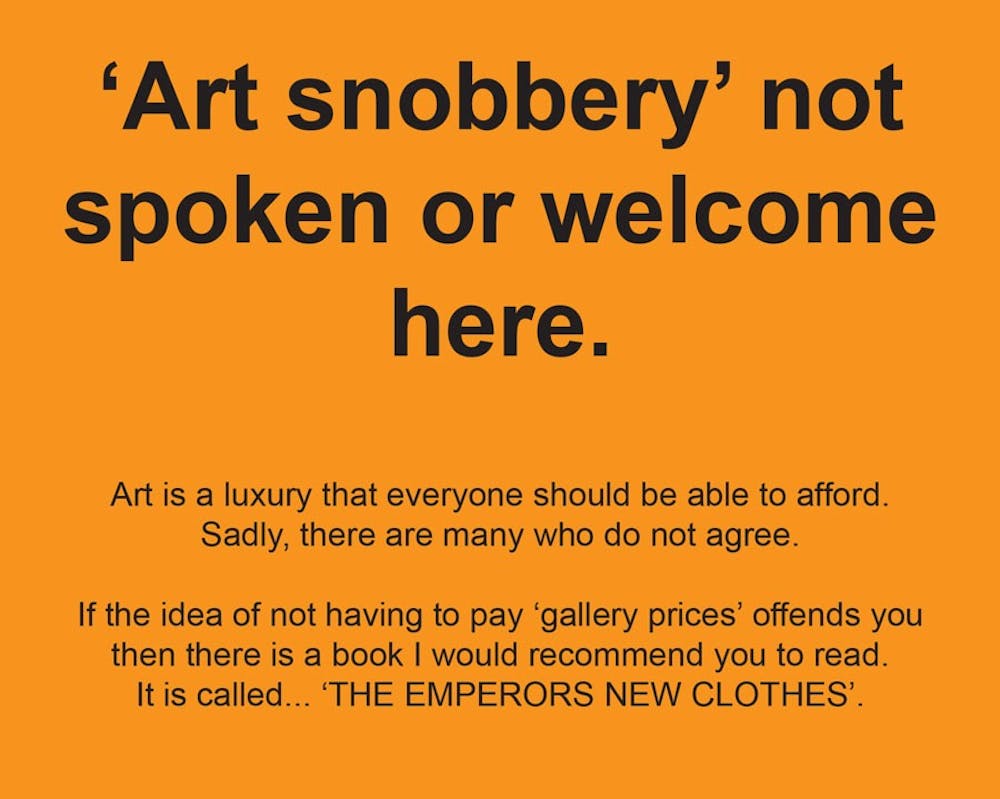

The other day, I noticed an artwork stall set up at the entrance and stopped to admire the pictures: intricately detailed depictions of the York Minster, the Shambles itself and other historic settings within the city. Then I noticed this sign:

While I puzzled over the meaning of that last idiom, a man popped his head above the stall. "Today you pay what you like," he said, accent thick with the sounds of Yorkshire. "From fifty pence to fifteen pounds, you'll get the set. That's nine pictures for you."

I was stunned. I blinked and wandered away, not really intending to buy. But then I just had to go back.

"I'm sorry, but may I ask your philosophy behind that? I'm very curious."

"O' course! There's nothin' so useless as art a person canna' understand, especially when he's got to pay gallery prices for it! My livin' comes from selling art in the galleries, but I understand that mine's a higher, more complex style as not many have studied. No need for 'em to pay full price. But if I can help them understand a bit o' York history, that's worth it to me."

The gentleman's focus was on the subject of his art. He portrayed it in a complex way, but anyone could appreciate the pictures. They depicted historic settings within the city, capturing the feel of the places. Towers of looming grandeur. Side-streets of cluttered surprise. His complex style didn't distract from the subjects: it enhanced them, unfolding them in a layered way.

Can we say the same for certain scrambled music styles or poetry that buries truth beneath vague themes? "Vivid and specific detail," Taylor's associate professor of English Dan Bowman always says. There's a reason for that!

As a writing student, I really appreciated the gentleman's mentality about art. Art should be understandable; art should be accessible. In chapel once, Steven Garber talked about "words that speak the truest truths of the universe, in language the whole world can understand." That's my problem with certain forms of fiction: if only critics can extract coherence from a piece, what's the point in sharing it?

Sure, there's value in self-expression and experimentation. And as readers, there's value in slogging through something difficult, and some subjects will naturally require higher levels of comprehension. But art shouldn't be designed to be difficult. It should be as accessible as possible, whether writing, visual art, music or any other form.

As the Yorkshire artist said to me, "There's nothin' so useless as art a person canna' understand!"